Mix Magazine has a great series titled Classic Tracks, where they chronicle the recording process of great songs of the past. In this case, it’s The Isley Brothers. Hard to believe they’ve been recording for 50 years!

This particular journey takes you from Teaneck, the Jimi Hendrix era and influence, signing with Motown, adding Ernie and Marvin to the recording with Malcolm Cecil & Robert Margouleff (Mi Casa Studios). An amazing story of how Ernie’s legendary guitar solo actually came to be. No ProTools here buddy.

“The mixes,” Margouleff adds, “were four hands on the console: Run the tape, if we made a mistake, leave the 2-track running, back up the multitrack and start it up again to right where we were before we made the mistake, then keep going, then go back and edit the 2-track.”

Be sure to check out other Classic Tracks from Mix Magazine. This was originally published on Nov. 1, 2003 by Blair Jackson.

By the time the Isley Brothers scored their 2 million-selling smash hit “That Lady” in the summer of 1973, they’d already been in the music business for nearly two decades. The first incarnation of this family band sprouted as a gospel group in their native Cincinnati in the mid-’50s, but in 1957, the singing brothers Ronnie, Rudy and O’Kelly (later just Kelly) Isley relocated to New York to be a part of the burgeoning East Coast doo-wop and R&B scene. They were signed to their first recording contract in 1959, and their maiden efforts for the label, including the moderate hit “Shout,” were produced by then-newcomers Hugo & Luigi, who would become a veritable hit-making machine during the next several years. Though not exactly a smash, “Shout” and revenues from the group’s exhausting touring regimen allowed the brothers to move the entire Isley clan to Teaneck in northern New Jersey.

“That Lady” (Ronald Isley, Rudolph Isley, O’Kelly Isley, Ernie Isley, Marvin Isley, Chris Jasper) 3+3 (T Neck 1973)

The Isleys’ second hit, in 1962, was “Twist and Shout” (later popularized by The Beatles); the next notable event in the band’s history was the addition, in 1964, of a hot young guitarist who went by the name of Jimmy James: This, of course, was Jimi Hendrix, who recorded his first sides with the Isleys and later — after he became famous on his own — would have a tremendous impact on the Isleys’ sound. In 1965, sans Hendrix, the Isleys signed with Tamla/Motown, and a year later, they had a huge pop and R&B hit with a tune written and produced by Holland-Dozier-Holland called “This Old Heart of Mine (Is Weak for You).” No doubt label kingpin Berry Gordy thought he’d found yet another group he could successfully mold in the Motown image, but it was not to be. Their next singles stalled on the charts, and the group felt overly restricted by the label’s formulaic approach. Still, in late 1967, “This Old Heart of Mine” became a hit all over again in England, and the group even moved there for a period of time to cash in on their unexpected success. But the following year, the Isleys moved back to New Jersey, formed their own label, T-Neck Records (initially as a subsidiary of Buddah Records), decided to produce themselves and almost immediately scored the biggest hit of their career — “It’s Your Thing,” still one of the funkiest soul workouts ever committed to vinyl, and which helped define the group’s style in the public’s eye.

Shout (1959)

“Twist & Shout” (Phil Medley, Bert Russell), Twist & Shout, (Sundazed/1962).

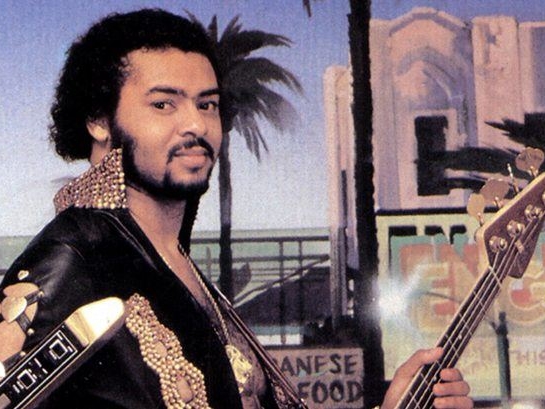

In 1969, too, the Brothers added some new blood to the lineup: younger brothers Ernie and Marvin, on Hendrix-inspired guitar and funky, funky bass, respectively, and brother-in-law Chris Jasper on keys. The days of faceless backup players for the three older singing Isleys were over. Now, it was truly a family band. The group had always had a keen ear for cover tunes, and in the early ’70s, they began to enjoy some crossover FM rock success with their soulful readings of such tunes as Stephen Stills’ “Love the One You’re With,” James Taylor’s “Fire & Rain,” Bob Dylan’s “Lay Lady Lay,” Carole King’s “It’s Too Late,” and even the politically charged combo of Neil Young’s “Ohio” and Hendrix’s “Machine Gun.” At the same time, their own songwriting continued to mature and incorporate the sounds of the full brotherhood.

“Lay Lady Lay” (Bob Dylan), Givin’ It Back (T Neck/1971).

While all this was going down, Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff were quietly becoming a much sought-after studio team, first for their creative work with early-generation synthesizers, and then for their overall studio engineering and production savvy. “I had been fooling around with synthesizers since the mid-’60s,” Margouleff says from his current L.A. base, Mi Casa Studios. “I got my first in 1966. It was serial number three or four from the Moog factory; definitely one of the first ever made. Bob Moog used to come and sit on the floor of my studio to fix the keyboards because the pitch would drift. By the time Malcolm and I found each other at Media Sound [in New York] in 1970, he was already an accomplished jazz musician, but also running the studio operation and maintenance department for Media Sound. We made a deal: He’d show me how to be a recording engineer if I’d show him how to use a synthesizer.”

“Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight” (James Taylor), 3+3 (T Neck/1973)

Permalink

Cecil and Margouleff became deeply involved in building new modules for the Moog instrument, and eventually they operated the largest synth in the world, nicknamed TONTO (The Original New Timbral Orchestra), and their electronic music system became the basis of a booming business for the duo, playing on records and soundtracks, and even making their own albums under the moniker TONTO’s Expanding Headband.

“We put out an album called Zero Time [1971], which was on Embryo Records, a vanity label owned by Herbie Hancock and distributed by Atlantic,” Margouleff says. “We didn’t even think that what we were doing was music in the pop music sense. But there was a big spread on us in Rolling Stone, and the bass player in Stevie Wonder’s band, Ronnie Blanco, saw it and picked up the album and then brought Stevie to meet us. Back at that time, we were making a lot of noise and a lot of people were coming to us. The thing is, the reason we became so indigenous in the business is the fact that we worked with everybody, whereas most of the other synthesizer players like [Morton] Subotnick and Wendy Carlos and Beaver and Krause mostly worked for themselves. We put ourselves in a major recording studio and worked for everyone who wanted to come through the doors; we made ourselves a ubiquitous comestible.”

“Don’t Say Goodnight” (Ernie Isley/Marvin Isley/Ronald Isley/O’Kelly Isley/Rudolph Isley/Chris Jasper) Go All The Way (T Neck/1980)

Permalink

Margouleff and Cecil’s introduction to Wonder couldn’t have come at a better time: the 21-year-old had recently earned his “freedom” from the Motown production cookie-cutter and given the right to produce his own albums. Working with Margouleff and Cecil allowed him to experiment to his heart’s content, with the three of them pushing TONTO — and Wonder’s musical palette — in exciting new directions. The first two albums they produced together, Music of My Mind and Talking Book, established Wonder as a formidable artiste and changed the face of “soul” music forever.

“For The Love of You” (Ronald Isley, O’Kelly Isley, Rudolph Isley, Ernie Isley, Marvin Isley, Chris Jasper) The Heat Is On (T Neck/1975)

So, it’s not surprising that the Isley Brothers, who themselves were becoming increasingly adventurous and independent in the early ’70s, would tap Cecil and Margouleff to work on an album with them. “I think the Isley Brothers got what it was that we could do,” Margouleff says. The pair continued to work with Wonder for the next couple of years — “Sometimes we’d be working with the Isleys and Steve would make us fly back immediately,” Margouleff recalls with a laugh — and collaborating on two more masterpieces: Innervisions and Fulfillingness’ First Finale. Wonder convinced them to move their operation to L.A., and though the first work they did with the Isleys was on the East Coast, eventually Margouleff and Cecil lured the group to L.A. so they could record at the Record Plant.

“Voyage To Atlantis” (Ronald Isley, Rudolph Isley, O’Kelly Isley, Ernie Isley, Marvin Isley, Chris Jasper) Go For Your Guns (T Neck/1977)

“Working with the Isley Brothers was much more business-like than working with Stevie,” Margouleff offers. “With Stevie, it was like living inside this world; it was a lifestyle, and we were really part of every aspect of the creative process: shaping the songs and getting sounds and all. We were much more on the outside of the Isley Brothers’ trip than we were with Stevie. They were a very close-knit family, and with them, we were more like hired guns. They’d show up at the studio and that’s where we’d see them. We didn’t go to their rehearsals, we didn’t socialize with them. They’d show up at the studio at 10 o’clock and work until 4:30. I remember them coming to the studio with a briefcase and paying us in cash,” he says with a laugh.

“That’s the way they were with live performances, too,” adds Cecil, who joined in on our three-way interview from his New York area home. “Rudy Isley had a .357 magnum that he had a license to carry around. I think the Isleys always got paid,” he adds wryly.

“Summer Breeze” (Dash Crofts, James Seals) 3+3 (T Neck/1973)

“But I don’t want to give the impression that we weren’t into the Isleys; we were. They were great to work with and really good musicians. I mean, some of the guitar sounds we got with them were absolutely rippin’!”

Indeed, one of the most remarkable aspects of the group’s sound, especially on “That Lady,” was Ernie Isley’s incredible, obviously Hendrix-inspired lead guitar line.

Cecil says, “What happened was, Ernie Isley was nine years old when Jimi Hendrix was playing with his brothers, and he was very, very motivated by Jimi. Jimi came to him one day and gave him his first guitar, showed him a few things and said to him, ‘You know what, when you grow up, you’ll be playing with your brothers.’ He was right, of course, and this totally changed Ernie’s life!

“When he came to us, he brought his Stratocaster and I took him over to meet Roger Mayer, who was another Englishman I’d known since my childhood in England in the late ’40s, when we’d go over to surplus stores on Edgeware Road in London to pick up old bits and pieces to build equipment, because that’s what we liked to do. There were all sorts of surplus equipment around after the war. Roger went on to become Jimi Hendrix’s guitar tech and then Jimi brought him back to the States. I bumped into him in New York and he helped me build some of TONTO, as well as working on audio treatments and [building] limiters.

“Anyway, he took Ernie’s guitar and completely re-modified it exactly the way Hendrix had his, and he also built him an Octavia box, which is part of what allowed Hendrix to get that screaming sound. And Roger taught Ernie how to use it. So, we essentially Jimi Hendrix-ized Ernie when he was 18. He was so blown away and enamored with it; he took to it like a duck to water. He’d be in there just playing and playing; he wouldn’t give it up.

“They were all marvelous musicians,” Cecil adds. “No one got away with anything. They were very disciplined and very self-policing in the studio. There were the younger brothers and the three older brothers —”

Margouleff: “And the olders made sure the youngers didn’t look up from their instruments, I’ll tell you.”

Cecil: “O’Kelly, who has since passed away, was like the lord and master.”

Margouleff: “He was the disciplinarian. Boy, nobody fooled around when he was in the studio! What he said went. I don’t know if it was because he was the oldest or what. But he was also a really nice guy.”

Cecil: “He was like a big Buddha.”

Margouleff: “And Ronnie, who has that incredible voice, was modest and shy and would hardly say anything. I always thought that Rudy was jealous of Ronnie. He was a good singer himself, but let’s face it, there’s no one like Ronnie. He’s just phenomenal.”

Margouleff and Cecil had so much clout in the business at this time that Record Plant owners Chris Stone and Gary Kellgren had a special studio built for them. “Malcolm and I were really like the first freelance engineers in the business out here,” Margouleff says. “Normally, studios had staff engineers. But we worked for the client; for instance, we represented Stevie’s interests in the recording. So what happened was we went and booked a studio by the year at the Record Plant. I remember we were up at Gary Kellgren’s Tudor house up on Camino Palamero and we stood up in the kitchen and he poured the Courvoisier to toast the fact that we’d booked the studio for a year. We clinked our glasses and immediately there was an earthquake! Remember that, Malcolm?”

Cecil: “Oh yes, it was quite propitious.”

Margouleff: “So, since we were going to be there so long, Gary and Chris Stone had a studio built to our specs. We had John Storyk, who had built the cases for TONTO, to work with us. The room itself was probably about 15 by 40. In the control room, we had an API console with a 3M 24-track, Ampex 440 2-track, LA-2As, 3As, 1176s, Universal limiters, four EMTs and these four huge Hidley monitors, because we used to monitor in surround when we recorded. We believed it was much easier to hear everything that way because you didn’t have to overlay one sound over another until you mixed to stereo. These Hidley monitors were so big that the rear ones stuck out through the wall into the hallway!”

Cecil: “They had to put rubber on them so people wouldn’t bang into them.”

Another unusual feature of the studio was the special bass trap on the roof above the control room.

“Between The Sheets” (Ernie Isley, Marvin Isley, O’Kelly Isley, Ronald Isley, Rudolph Isley, Chris Jasper) Between The Sheets (T Neck/183)

The engineers say that the Isleys came into the studio very well-rehearsed, so the recording of basic tracks was quite straight-foward. “They knew exactly what they wanted to do,” Cecil says. “They had a complete plan when they walked in the door.” On “That Lady,” which was actually a slinky re-working of a mid-’60s Isleys tune originally titled “Who’s That Lady,” the basics consisted of Marvin’s bass line, a rhythm part by Ernie, electric piano from Chris Jasper, Truman Thomas’ organ and drums from George Morland. Vocals, additional keyboards, congas (by someone credited only as Rocky) and the famous lead guitar line were added later.

The lead guitar part alone took several tracks: “We had the Octavia box, a direct from the guitar, a Berwin noise suppressor, limiters, all sorts of things going,” Cecil says. “The Octavia made a tremendous amount of noise, so we had to use whatever means were available to minimize it. One small turn of a knob and all the parameters would change. It was trial-and-error. Ernie would play a line and we’d try different sounds on it. He’d come back in the control room and we’d listen to it, decide if it was right. Then, when it came time to mix, because we had four or five tracks for the guitar, we’d find the blend that worked best. Ernie was always very cooperative, and he could really play.”

“The mixes,” Margouleff adds, “were four hands on the console: Run the tape, if we made a mistake, leave the 2-track running, back up the multitrack and start it up again to right where we were before we made the mistake, then keep going, then go back and edit the 2-track.”

“That Lady” would become a double-Platinum smash for the Isley Brothers in the summer of 1973, and the popularity of that single and the nearly six-minute album version (where Ernie really cut loose) propelled the group’s 3 + 3 album (named for the three original members and the three newer additions) into the Top 10. “What It Comes Down To” and the band’s version of the Seals & Crofts chestnut “Summer Breeze” were lesser hits. By the way, Margouleff and Cecil schooled Jasper extensively on the use of synthesizers and, not surprisingly, it became an integral part of the Isleys’ sound for a while, though not on “That Lady.”

Cecil and Margouleff would make a couple more discs with the group in the mid-’70s, including co-producing The Heat Is On, which contained the Top 5 hit “Fight the Power.” The Isleys would have their share of ups and downs during the next decades, including a period when Ernie, Marvin and Chris Jasper broke off to form their own group. O’Kelly died in 1986, and Rudy left to become a minister. But the group has shown amazing resilience and staying power, in part because Ronnie Isley has one of those voices, but also because they continue to choose their collaborators well; these days, the likes of R. Kelly and Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis are helping keep the group up-to-date. In the current decade, the band, now fronted by Ronnie and Ernie, has continued to notch hits, such as the 2001 intoxicating “Move Your Body,” which almost sounds like an updated version of “That Lady.” Hey, why mess with success?

RELATED POSTS

November 4, 2010

Ron Isley – No More

June 7, 2010

R.I.P. Marvin Isley

December 3, 2009

Maxwell performs “Lady In My Life”

November 7, 2014