Our thoughts and prayers go out to the Taylor family.

From the Chicago Tribune:

Koko Taylor more than once said she hoped that when she died, it would be on stage, doing the thing she loved most: Singing the blues.

She nearly got her wish. The Chicago musical icon died Wednesday at age 80 of complications from gastrointestinal surgery less than four weeks after her last performance, at the Blues Music Awards in Memphis, Tenn. There she collected her record 29th Blues Music Award, capping an era in which she became the most revered female blues vocalist of her time with signature hits “Wang Dang Doodle,” “I’m a Woman” and “Hey Bartender.”

Taylor died at Northwestern Memorial Hospital 15 days after her May 19 surgery. She appeared to be recovering until taking a turn for the worst Wednesday morning, and was with friends and family when she died.

“Koko Taylor’s life and music brought joy to millions of people all around the world and Chicago is especially honored that she called our city her home for more than 50 years,” Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley said. “The strength of her style was formed in the night clubs of Chicago’s South Side and she carried that spirit with her wherever she went. She was an ambassador for our city and truly was the queen of a kind of music that makes people think of Chicago whenever they hear it.”

Among those with her Wednesday was Bruce Iglauer, owner of Chicago-based Alligator Records, who was her producer, manager and friend since 1974.

He recalled that Taylor had a similar surgery in 2004 and was on a ventilator for nearly a month. “The doctors were very discouraged then about her coming back, and she willed herself back to life,” Iglauer said. “We were hoping she would do the same this time.”

Born Cora Walton in 1928 in Memphis, Tenn., Taylor literally got up off her knees to become a blues icon.

Growing up on a sharecropper’s farm outside Memphis, young Cora and her three brothers and two sisters slept on pallets in a shotgun shack with no running water or electricity. By the time she was 11, both her parents had died. She picked cotton to survive, and moved to Chicago in the early ’50s to be with her future husband, Robert “Pops” Taylor, who died in 1989. She found a job working as a domestic, scrubbing floors for rich families.

She had sung gospel music in church while living in the South, and on weekends would attend the blues clubs on Chicago’s burgeoning South Side scene, the heyday of Chess Records and such stalwarts as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and Willie Dixon. She would occasionally sit in and caught the ear of Dixon, who approached her in the early ‘60s about recording one of his songs, “Wang Dang Doodle.”

“I didn’t know Willie Dixon from Adam’s house cat,” Taylor recalled in an interview with the Tribune. “But he says to me, ‘I love the way you sound’ and, ‘We got plenty of men out here singing the blues, but the world needs a woman like you with your voice to sing the blues.’ ”

Taylor’s 1965 hit recording of “Wang Dang Doodle” launched her career, and established her sound: a gruff, no-nonsense roar that was the female equivalent of Howlin’ Wolf’s baritone growl. By becoming a band leader and a powerful voice in a male-dominated scene, she broke down barriers for many female entertainers who followed.

“Some of the lady singers who were working little local clubs, or maybe just attempting to sing in choirs and churches, they got into the blues scene because of Koko,” said Bob Koester, founder of Delmark Records. “Zora Young, Big Time Sarah, Shirley Johnson – they were inspired to try to come out and sing blues because of Koko’s success. Without Koko, that might not have happened.”

But when Chess folded in the early ‘70s, Taylor was back where she started, scrapping for a living.

“It was a devastating time for my mom,” Taylor’s daughter, Joyce “Cookie” Threatt, once told the Tribune. “Then she met Bruce [Iglauer]. It was like God put him there.”

Iglauer had never worked with a female vocalist before on his fledgling label, which was dominated by guitar-playing men. But he was impressed by Taylor’s moxie and her sound.

“She was of the same generation as Muddy and Wolf, she had those [Mississippi] Delta roots,” he said Wednesday. “Even though she had been living in Chicago since the ‘50s, her music was still deeply rooted in the South. She had that rhythmic sense, that sense of where you lay the words and how the band locks in around the singer, that intensity of people who have lived that life.”

Taylor was already a distinctive artist when she came to Alligator, and with Iglauer’s help began exploring a more vulnerable side to her persona on select ballads such as her epochal version of the Etta James hit “I’d Rather Go Blind.” Even when recording other people’s material, the singer put her idiosyncratic touch on it, usually singing it a cappella in the studio, with the musicians following her.

Taylor never adopted the blues lifestyle of hard drinking and philandering that consumed some of her peers. She was a devout woman, but at the same deeply appreciative of how the blues communicated honestly and directly about everyday life.

As her daughter once told the Tribune: “She grew up singing in [the Baptist] church in Memphis, and people come into church to get washed. They don’t come in there already clean.”

At the same time, she was not one to mince words. She could be devastatingly direct with anyone who crossed her.

“She was meticulous about her music, so if her band screwed up, they would hear about it,” Iglauer said. “She would not bite her tongue.”

For her, the blues was life. She bounced off her death bed in 2004 to write and record another album, the aptly titled “Old School,” released in 2007 on Alligator. It would prove to be her final recording, though Iglauer said that in recent months Taylor was calling him and singing new songs over the phone.

“She was scheduled to go to Spain next week,” he said. “She was still performing. At the Blues Awards in Memphis a few weeks ago, she was absolutely glowing. She would be exhausted standing by the edge of the stage, but when the lights went up, she would hop up and dance as soon as the music started. She would always say, ‘If I can brighten one person’s day with my music, that’s what I live for.’ ”

Survivors include her husband, Hays Harris; daughter Joyce Threatt; son-in-law Lee Threatt; grandchildren Lee Jr. and Wendy; and three great-grandchildren.

Funeral arrangements are pending.

greg@gregkot.com

The Tribune’s Howard Reich contributed to this report.

RELATED POSTS

November 22, 2010

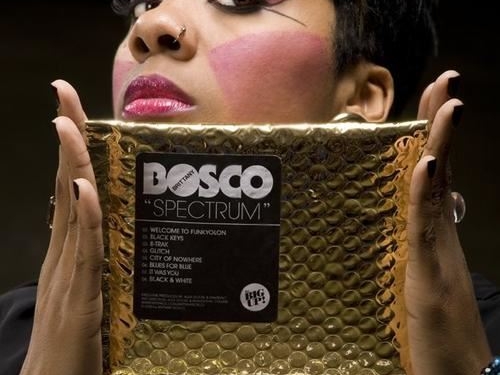

GFM Spotlight-Russell Taylor

June 22, 2010

The Jacksons-Blues Away

June 24, 2010

Come meet Russell Taylor Tonight at Moods Music

June 14, 2010

[…] Grown Folks Music » Blog Archive » Chicago blues legend Koko Taylor dies at 80 >> http://grownfolksmusic.com/?p=3033 >> […]