Photo Credit: Jirard Foto

Special thanks to Sarah Crisman for conducting this excellent interview with Dallas born and bred musician Geno Young. Also checkout the track “Shoulda” after the jump that is available as a free download today from Geno.

Geno Young was born and bred to be a revolutionary soul artist. That’s how we do in Dallas. Or as our neighbors, Erykah Badu and producer Jah Born like to say “Dirty Always Live like a Soldier.” Yet few truly understand the contributions the Dallas community has made to the music industry at large – from Gospel, R&B, to Soul and Jazz, Dallas cats are playing the game on a different level compared to other urban hubs.

Shoulda by GrownFolksMusic

Geno came up in the anointed halls of Dallas’ Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts alongside other game-changers like Badu, Roy Hargrove, and Norah Jones. After graduating from Arts Magnet, Geno followed in the footsteps of Donny Hathaway to study music at Howard University ‘round about the same time fellow Texan, Chris Dave was hitting the boom clacks and books. After school, Geno toured the world as musical director, arranger, and producer for Erykah Badu. He wrote and produced the hit songs “Times a Wastin’” and “Orange Moon” on her 2001 release- Mama’s Gun. His 2004 solo debut, The Ghetto Symphony garnered attention for him around the world and his recent sophomore effort, Ear Hustler has renewed a frenzy of fans ready to emerge from the underground and shout from the roofs what “Shoulda” been known all along – Geno Young is one hustler you can trust your ears to entirely.

(L to R): Gino “Lockjohnson” Inglehart, Geno Young, Deonis Cook, and Shaun Martin. Photo Credit: Jirard Foto

Sarah Crisman sat down with Geno in Downtown Dallas to get to the heart of this Deep Soul Revolution brewing in their shared hometown to explore where it started and what it will take to make the world(and the neighbors) stand up and take notice.

Let’s explore your Arts Magnet years to give everyone a more extensive look at why we keep using words like “revolution” when we talk about the Dallas Soul community (lest our message be construed as delusions of grandeur and hometown pride). Looking back at your time at Arts Magnet, what element had the greatest impact on you?

I look at Arts Magnet as a breeding ground for a lot. It was such an open environment; it really fostered the creative aspect and collaboration. That sounds obvious, like a school like Booker T should offer that, but you see these teachers that a more like professors, pushing you to experiment and do your own thing. Always encouraging you to put a small group together, get a combo together, or suggesting “why don’t you write a song?” When you are in an environment like that at 14 you can’t help but develop a sense of musical freedom, artistically. I think that’s why the bond is so tight amongst the musicians –look at my relationships with Shaun Martin, RC Williams, and Robert “Sput” Searight. We all ended up working together. I think it was the professors. Everyone there could do everything. Literally, go in and see Erykah there and know she was just Apples from the dance department, but also knowing she did music and it wasn’t in any way weird; it wasn’t a surprise. You do what you do. Teachers would say ‘oh, yeah, she sings, too. Come sing for her.” A music teacher or a theater teacher would come to a student

and say ‘you really have a knack, you have charisma, and I want you to be in the play this semester/the mime troupe/improv troupe.’ This fostered a camaraderie that radiates in us now.

You mention your Grammy-nominated peers, Shaun Martin, RC Williams, and Sput. Who else were you coming up with in school?

I was in the Lab Singers with Myron Butler – he was the pianist for the Lab Singers. Sput was the drummer in our small group, and Braylon Lacy. I was playing and arranging and that was how we all got introduced to each other, really. I remember knowing Sput was a drummer, then going from my classical piano lesson into a practice room and hearing him play piano and I was like “what the hell? He plays like that, too?” Here’s Sput sitting in a jazz vocalist’s class with Myron Butler one minute and then writing all these Gospel tunes and pop tunes outside of that. When we got there Erykah and Roy were seniors, so I saw Roy go off with Dizzy Gillespie when I was a freshman.

Did it occur to you that not every school is swarming with talent like that?

It did. And you know what is not talked about is the influence of Arts Jazz — Booker T had its own festival with major players like Dizzy Gillespie and George Benson came to the Meyerson. It was a serious, weekly festival that rivaled the IAJE (International Association of Jazz Education) – and it was right here in Dallas! Artists like Maynard Ferguson would come and do clinics for the public. People traveled in and they had concerts every night at the Meyerson. It was that kind of stuff – when Roy was playing with Dizzy Gillespie and then Dizzy was here and now they’re taking him away.

That would be difficult to take for granted. I know, personally speaking, having lived in Dallas for 18 years and in the music industry for five years, it is hard to remember at times that it’s not like this everywhere. You talk about your classmate, Roy Hargrove, being “taken away” by Dizzy Gillespie –did you appreciate at that point the cultural impact that you yourself could have?

Not then, I think that was later. I knew the music we were doing was on a different level in all aspects. In classical or choral music, you knew those singers were good. Look at Myron Butler – he’s a Grammy Nominated Gospel recording artist. I knew that no matter what we did we had this foundation. I don’t think I appreciated it until later, until I got to college and realized it was the same stuff we did in high school. Not in the snooty way, but in the “I actually am prepared” way. These teachers were dope in the environment of letting us create while having a theory class, balancing that with academics, and having a show – it didn’t faze me. It’s just what you do.

You were at Howard for college, how did you find the artistic approach and the pool of talent to be different from Dallas?

The funny thing was that it was different, the people there were monstrously talented but it wasn’t thesame – how do I say this?

Soul?

Exactly! It wasn’t the same soul. Interestingly, the people that did have the same soul were Texans. When I got there, Chris Dave was there. He went to the performing arts school in Houston and here he was the baddest drummer in the world, and I’m from Texas and I went to a performing arts school in Dallas. So I got the sense that there was something going on with Texas.

What brought you back to Dallas?

I came back to Dallas after I graduated– Howard was good, I was in a good place there, but I came back to work at Friendship West Baptist Church as the Assistant Director of Music and eventually became the Director of Music there. Shaun Martin was the organist there and just getting into North Texas, and we had grown up together. Initially I was going to Grad school in Southern Cal or go to New York, but I decided that was a cool gig. So I came back home and within six months I was singing with Erykah. That’s how quickly it turned around.

Which brings us to my next question! You began singing with Badu and worked on Mama’s Gun with the crew you had gone to school with — what was it like to have that sort of reunion? How were you different and what were you learning from each other that you had perhaps grown into during those years apart?

I think the only difference was that I had started singing background first, me and N’Dambi. Do you know Madukwu Chinwah? He’s one of the fore fathers here, of Nigerian descent. He produced “Rim Shot” and “Certainly” on Baduism – he’s a guy from Oak Cliff. The story goes that when I came home, Erykah called Chinwah and asked if she should take “Junebugg” on the road with her and he said she would be dumb if she didn’t.One night while Erykah was still writing Mama’s Gun, she was singing at the Velvet Elvis uptown, andN’Dambi was performing off her first album. Erykah came to me and asked me to put a band together to vibe with her that night. I grabbed Gino “Lockjohnson” Inglehart, Braylon, Sput on percussion, Shaun, RC, and myself. After that night she walked off stage and sang a demo version of “Green Eyes.” She came to the edge of the stage and said ‘put a band together for me.’ It was magical. I think the only thing that made me different was that she put me in an organizer role. We were still boys. Even though I hadn’t played with everybody in awhile (except for Shaun and Gino at church), hadn’t played with RC or Braylon since I graduated, but they were the first people I called – The Dallas crew. So we put a band

together and that’s how we lead up to Mama’s Gun. Yes I was in a new role as Musical Director, but I was just going with what I knew – the guys here.

It’s like what you were saying about Howard: Arts Magnet prepared you for that moment. It wasn’t something to be grasped, it was just ‘call up the guys’ and do what you do.

I’m giving you the real scoop. She said ‘put a band together and I’ll come here you guys play.’ I put together two of everything. Because I had been on the road long enough to know: two bass players (Braylon and Keith Taylor); two keyboardists (myself and Shaun); two drummers (Gino and Peebody); and a horn section (Jason Davis and Leon Devers). She came to rehearsal and sat for ten minutes while we played a couple songs, she switched out drummers and bass players, and was like ‘cool.’ Didn’t say anything else, left, and after that we were the band!

You mentioned your days spent touring — how do you see Dallas artists handling themselves differently out in the music industry at large? How are y’all approaching things different?

I don’t know if it’s some level of Performing Arts connection, some kind of schooling there, maybe? There is a lot of professionalism. There is a lot of hard work. For anybody who doubts it, I have never worked as hard with anybody as I worked with Erykah. Nor seen anybody work as hard as her – her work ethic is –

They Sleep, We Grind.

Really. It’s phenomenal. It’s very meticulous. Touring with her when we did taught us a lot. I think the Dallas folks just have a level of professionalism and I’m not really sure where it comes from. Maybe it’s a combination of Booker T and we could also attribute the church with a lot of that. People look at that band and other bands in Dallas like The Grits, Ivory Jean, even with Deonis. People look at that and say ‘oh my god, why is it so tight?’ Because Sput and Deonis have been playing together forever with God’s Property; and Braylon and Shaun and all of us have been playing together for 20 years.

You talk about professionalism and the church connection, perhaps there is a high level of accountability there? Not to mention that it’s probably pretty hard to bullshit someone you’ve known since you were a kid. Even working on the level that y’all have achieved, there’s always someone like that around to keep you in line.

That’s very true. They know you better than that.

What did Erykah teach you about breaking out on your own as a singer/songwriter?

I credit her with a lot. One: the work ethic. When I started working with her and we put the Dallas band together, I felt like that was the point when she became the most free. With Baduism she was still growing and the band around her was still growing. They weren’t from Dallas so I don’t think they felt her like Dallas folks did. I learned how to conduct the business and how she had her company set up. I look back and going on the road in ’98 and how she had her company set up, the way in which we were paid, the way in which we were handled. There were a lot of first class things going on and she hadn’t been in the game long. We were always treated well. We didn’t know it at the time because she kept us so tight, but she encouraged a lot of creativity. We thought it was creativity under the umbrella of the Badu thing. But really, in essence, she meticulously added a piece here, a piece there, to grow things and do an album. I learned a lot about how to be an artist, really.

You wrote and produced “Orange Moon” and “Times a Wastin” on Mama’s Gun– that seems to be a

good example of her encouraging your creativity.

True. They both happened very organically. We all had writer’s credit on that: myself, Shaun, Braylon, Erykah (of course) because it happened so organically. She said ‘okay, guys, I have an idea and it sounds like this: I’m an orange moon.’ Shaun and I looked at each other and said ‘ok, key of E Flat.’ It really happened that organically and we developed it over time and gave it a mood and she did her Erykah thing on it and it was like magic. “Times a Wastin” is actually an interesting song because she had the idea to do the bridge – Oh baby we need to smile. She had that idea and the basic groove of that song came from a session we did at Camp Wisdom with Guru. She brought Guru down to Dallas to work on the song that she did on his Streetsoul Vol. 3 – the “Plenty” song. We just sat in a room with Guru for two days. You asked how we learned stuff. She would sit there with a mic, Guru would sit there with a pen and pad. She would dictate grooves or tell us a drum pattern or hear a bass line. We sat there and created for two days. We’d just switch grooves, or it would be “Shaun do this,” “Junebugg do that.” From those two days of music Guru and Erykah picked an eight-bar loop. We came away with “Times a Wastin,” a song for him, and came away being even tighter and knowing how to create in a room together.

Since your work with Erykah, you broke out on your own to create two cult-favorite albums, 2004’s

Ghetto Symphony and 2010’s Ear Hustler. How have your views on this revolution changed at this

point? Have you felt frustration?

Definitely. Definitely. We still haven’t told the story. I think that what separates us from – I don’t care who it is – what separates us from the cats in Philly (or no matter where they are) is the story: the high school camaraderie and growing up in church; Shaun, RC, and I living in the same neighborhood; my parents going to college with Sput’s parents. These connections are the story that hasn’t been told. Look at Roy Hargrove – no, take it back further – look at Edie Brickell and the New Bohemians, Roy

Hargrove, Norah Jones, Erykah Badu, Kirk Franklin, N’Dambi. Seriously, N’Dambi is the start of a lot of what goes on in Indie soul music. Period. She was first. Before Eric Roberson, it was N’Dambi out of her house in Oak Cliff and along with her manager, Odis Johnson, laid the foundation of how to do it. How to do it independently, how to get overseas with no Twitter, no social networking. When people say the Indie Soul scene is on the East Coast. Whenever these artists dropped from Dallas the game changed. Kirk changed Gospel music. Erykah changed Soul music. There were no young jazz lions before Roy. Norah was a totally different feel of music that won Grammy’s and crossed over to mainstream and nobody ever makes that high school connection. You don’t even have to deal with the high school, just look at God’s Property. That was my class at Booker T and they changed Gospel. I don’t want to hear crap about those other cities — I want to hear Dallas, specifically.

Sarah Crisman is a writer, talk show host, and music advocate living in Dallas, Texas on purpose.

RELATED POSTS

May 25, 2010

Leela James-My Soul

January 16, 2011

Aaliyah- Young Nation

November 24, 2009

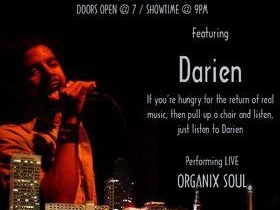

Organix Soul f/Darien

November 16, 2010

[Pics] 2nd Annual Soul Train Soul Music Gifting Suite!!

August 2, 2010