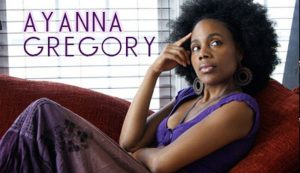

Just in time for Black History Month, Grown Folks Music spoke with artist/activist Ayanna Gregory. We talked at length about how her father’s legacy influences her activism and her plans to bring forth healing to the children of other civil rights leaders. As the conversation turns to her artistry, she discusses finding her place in the movement through music and giving herself permission to be herself in her music. Lastly, we talk about her one-woman play– Daughter of the Struggle– which the presents the movement through the eyes of a child, and of course she answers the question, “What is Grown Folks Music?” Read below and enjoy.

Because Daddy Did That

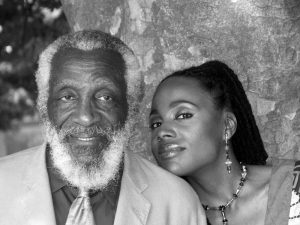

GFM: I’d like to start off for the Grown Folks out there who don’t know that your father is Dick Gregory. Obviously, you are your father’s child and I think I heard you say that you’re not just representing yourself, but you represent your mother and your father. Obviously he influenced your journey and your growing up and the shaping of you, but how has his passing influenced or informed your direction now?

AG: That’s a great question. I think that in his passing I feel a greater sense of urgency and a greater sense of responsibility to do this healing work. So, the work is really the same because this has been the path that I’ve been on my entire life. But, in his passing so many people have been reaching out to the family from around the world. I knew what he meant to people, but I didn’t realize how many people thought of him as immortal even in physical form. I found that in talking to people a lot of people felt scared, because he was almost like their living black superhero. It was almost like, ‘Well, as long as he’s here we’re alright.’ I didn’t have a concept that in his transition that there would be people sort of looking to us like, ‘What are we going to do now? What are y’all going to do now that he’s not here in the physical anymore?’

I thought about the fact that when my dad was here he never stopped. He didn’t make time really to rest. He didn’t make time for himself. His entire adult life was given to humanity. There were no breaks. And so days when he may have been tired where that black grandmother from Memphis, Tennessee called to talk about her grandson who had been arrested and thrown in jail wrongfully– he was going to stay on the phone with her for three hours– even though he was about to get on stage a few hours later. I thought to myself, ‘Huh. I’m not my father. I’m meant to walk my walk.’

But at the same time I thought, ‘I do have a responsibility to step my energy… to step up my level of endurance… to step up my commitment really.’ In filling a space… I could never fill his space, but I think that he was very intentional in what he downloaded into me and into his other children. Me being one of the more visible children– I know a lot of folks look to me. Even at the Martin Luther King celebration at Ebenezer [Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church- Atlanta, GA] when folks in the room realized I was his daughter it was almost like they just needed to hold me and touch me because it was the closest they could get to him. I thought, ‘Yeah, if my feet are tired it doesn’t matter. I’m gonna stand until everybody in this room hugs me and shares their story because they need to do that.’ I think there’s just a little bit more commitment to endure even when I’m tired because Daddy did that.

Keepers of the Legacy

GFM: I’d to keep talking about that theme of healing because I’d like you talk to us about the non-profit [organization], The Keepers of the Legacy because that struck me when you were talking about the human healing from the trauma of the movement. Talk about what that is.

AG: That is something in the making. We have not created that non-profit yet, but we’ll be creating it in 2018. My youngest brother, Yohance and I a few years ago were talking. We’re the babies of our family. Out of ten children we’re the two youngest. He’s the actual youngest. I said to him, ‘You know Yo, we came out the way people thought we would. I said, ‘We had the best of everything. As the babies of the family we got to get everything after all the kinks had been worked out.’ My older siblings didn’t have that luxury. My older siblings were flying by the seat of their pants with my parents in the ’50s and the ’60s as they were figuring it all out. We came in the early ’70s where we sort of got the best of everything. We got the sense of commitment to the movement, and at the same time we didn’t have to live in the same level of fear that they had to live in because of the immediate danger that the family was in. I was saying to him, ‘We really represent the best of what children of the civil rights and human rights movement really look like.’

When I say that I mean that often times I think that when people are inundated with a certain life, sometimes they rebel. Sometimes the trauma of it is so deep that they can’t really deal with it. I did a documentary [Born in the Struggle] that was basically focusing on the children of the movement by a brother, Dr. Kamasi Hill, out of Philadelphia. What I found is that so many of the children of [the movement]… many are in a lot of pain. Some have a lot of resentment because they lost their parents early or even when their parents weren’t around they really couldn’t access them. Some went in a completely direction. I realized, Wow. That never really happened with us. Yes, we rebelled– certainly around the health and nutrition aspect. We weren’t trying to have it when dad was locking down the sweets and the meats and all of that. But, we came back around to recognizing that his wisdom prevailed.

I say all that to say that we grew up knowing at least on a surface level all of the children of [the movement]. We would come to the marches. The March on Washington– I wasn’t alive in ’63 for the original one, but 1983 was the 20th anniversary. We came to all of the major marches. The whole family did. I remember as a little girl meeting the King children, meeting Jesse Jackson’s children and Andrew Young’s children. I didn’t know them well, but we knew them. We grew close with some. Martin Luther King, III has always been extremely close with our family. Dr. Bernice King– who invited me to perform at the Martin Luther King celebration at Ebenezer– I didn’t know her well, but was very happy to connect with her and talk with her. At my father’s homecoming when I spoke with Ilyasah Shabazz– Malcolm X’s daughter and Rena Evers– Medgar Evers daughter we talked about the fact that this has just been a long time coming. It’s time for us to come together and spend time together collectively and talk and really do some healing sessions.

Our stories are very different but also very much the same. Let me be clear. The Gregory’s did not go through what the Kings went through, what the Evers went through and what Malcolm’s children went through. Our father was not taken from us [or] murdered. None of that happened. We got to see our father play out a natural life and live at the age of almost 85. In that way our lives were not the same. But then in other ways… we dealt with the death threats. We dealt with the assassination attempts. We dealt with the phone taps and all of that. There’s just so much history that we have among us to share and a lot of healing that still has yet to be done. The Keepers of the Legacy organization is really going to be about how do we continue this work, but also begin to form some alliances to say, ‘We don’t have to do this by ourselves.’ We can form a collective of love, of healing, of support and inspiration for each other and inspire others to do the same.

A Place in the Movement as an Artist

GFM: At what point did your artistry present itself and stir you to a point where you could not ignore it?

AG: I would say two distinctive times in my life. The first time was when I got to Howard University. I had just transferred from Hampton University. It was 1990. I think I was 18 or 19… probably 18. That was at a time in Washington D.C. where it was like a renaissance of the ’60s. It was a beautiful time to be at Howard. There were so many powerful student movements going on. I fit right in. I was like, “This is my world.” I became a student activist. That was during the time of the first war in the Persian Gulf. The first [President] Bush was in office. Howard was just a powerful force to be reckoned with. It was around the time of the powerful messages in music and in hip hop with Public Enemy and X-Clan and everybody. I became one of the voices of the student movement. I became a voice they would call on to sing… to sing the freedom songs… to sing the protest songs. That was the first time that I realized I had a place in the movement as an artist.

As I became recognized as this singing voice with a particular connection to the movement more and more people started to call on me for that. At the time, I had only sung acapella. I didn’t even have a concept of singing with a band. I wasn’t in the department of fine arts so I never pursued any training around music. I knew that I could sing, but I didn’t have any real skill set around musicianship. It wasn’t until the early to mid ’90s that a brother named Mamadi Nyasuma, who had formed an ensemble called 2000BLACK, which was very much about edutainment messages in music and it was a combination of go-go, hip hop, r&b, soul [and] reggae. He pulled me in and said, ‘Hey, you have an amazing singing voice.’ I was scared, because I was like, ‘I don’t know what it is to sing with a band.’ I never had to keep time. I never even had to stay on the same key because I was singing acappella. That gave me my first context of understanding music differently and understanding it in the context of singing with a band and understanding chords and harmony.

I sang with 2000BLACK for some years and then when I graduated from Howard I was actually planning to come to Clark [Atlanta University] for grad school. I’d studied sociology and African Studies and I thought I wanted to be a part of helping to save the world, but it was still a big abstract idea. I didn’t know how I was going to do that. I get into the schools, I stick around in [Washington] D.C. and I started substitute teaching. I began working as a counselor at an after-school program. At this particular after-school program in [Washington] D.C.– it was called Martha’s Table– the teenagers would come to us after school. We’re trying to help them with everything from their homework to life skills and dealing with some of their emotional life stuff as well. I realized that they had their headphones on. A lot of times they’re not really paying attention. They’re in their own world. We’re trying to regroup thinking, ” Well, how we get the headphones off so they’ll pay attention to the lesson?” And it just clicked. I said, ‘If you can be the message in their headphones, Ayanna, that’s it. You’re moving in the route of education and social work and you want to counsel and all of that– well you can do that in the music.’ How better to reach them than where they’re at. They love music. They want the beat? Give them the beat. Give them the message.

That’s when it really clicked that I went all the way around the world only to come back home. The Creator doesn’t make it difficult, but often times we do. In my mind, this musical gift had been there my whole life and I thought it was a hobby. Then I came back around to, ‘No, this is the life work. This is your passport.’ In fact it was. Every school I went to my ability to sing is what allowed me to connect with those children. Once they realized, ‘Oh she can sing,’ then they listened to whatever else I had to say.

360 Degrees of Ayanna Gregory

GFM: There’s another side of your artistry. I know that all of your music is not necessarily rooted in activism, because I heard you that your songs allow you to tell on yourself. Tell us what you mean by that.

AG: When I wrote my first album, Beautiful Flower, as much as I still love that album I recognize that at the time that the album was put together I was not yet comfortable with 360 degrees of Ayanna Gregory. Growing up as Dick Gregory’s daughter I didn’t give myself permission to show up publicly as vulnerable… to show up with contradictions… to show up with any sensuality. I didn’t give myself permission to show up as anything but educational and powerful and as an activist. Consequently, the Beautiful Flower album didn’t have any romantic love songs on it except one. In my mind I said, ‘Everybody’s singing about love. I need to pay attention to the things people aren’t talking about.’ It was like my entire musical world was dedicated to freedom songs ultimately.

Then it dawned on me, ‘Are you free? It seems to me that you are a slave to and locked into this concept that the world has of you and that you’re afraid to step out of.’ My friends and people who knew me well would be like, ‘You’ve got some sides you ain’t talk about on stage.’ My friend, music director and producer of most of my albums James McKinney– he’d laugh at me. He said, ‘Yeah, you got this queenly thing going on on stage, but that ain’t everything.’ Initially I would get mad like, ‘Whatchu talkin’ ’bout?’ Then I said, ‘Yeah, he’s right.’

There’s a song that I wrote a few years ago titled “Now”. I call it my healing anthem because it was probably the first song that I wrote that allowed me to be as I am… vulnerable and flawed… as well as all of the other things. The lyrics [say]

“Always played the victim role

To satisfy my need to be right

Always feeling so alone

Neglected by the men in my life

But they were just doing what I wanted

They were just giving what I gave

But now I want the real thing

So, let it be a new path that I pave

Afraid of my destiny

Who am I to live too big

The universe keeps blessing me

But every single time I renege

Filled with insecurity

Sabotaging royalty

Planned mediocrity

Self-fulfilled prophecy

I’m so afraid to let them see who is she”

I was so tired of presenting on the outside as complete, sure, ready and powerful and on the inside feeling like a shell of myself. I was continuously dumbing down my light because I didn’t feel comfortable in an environment that wasn’t set up for us. I grew up in an all-white environment in Plymouth, MA. I was used to sort of trying to hide my Ayananess in order to blend in, and there was no way I could ever blend in. I just couldn’t do it. None of us really do blend in fully when we are our full selves, because we’re not supposed to.

It was me finally giving myself permission to say, ‘You don’t have it all figured out, Mama. Let’s talk about that.’ It was me finally giving myself permission to say, ‘Sometimes, I don’t feel sure. Sometimes, I feel sad.’ Sometimes, I look at the pattern and the choices I’ve made in relationships and say, ‘Hmmm… would someone who knows herself have chosen that relationship?’ It was my opportunity to say, ‘Let’s talk about that.’ Let’s talk about that fact that in choosing relationships I’m also choosing reflections of myself. So, it was finally coming to terms with those recognitions about my life. It got fun. I was like, “Man, it’s fun to tell on yourself.’ Once I defanged it… the big thing of [gasp] , ‘What if you tell people that!’

In working with young people… that was the other thing… I didn’t allow myself to be three dimensional because it was like, ‘I don’t want them to know that I did that.’ But it was like, ‘Okay wait a minute. You’re talking to young people about integrity and yet you’ve been in a relationship with a married man. But you can’t talk about that, huh? Okay, but you’re living with it and you’re standing before the universe that’s already aware of it. So, what are you really afraid of?’ That’s when it was like, ‘Alright. Let me really allow myself let some of this stuff go so that I can stop beating myself up on the inside and let it go and recognize I’m human and I get to shift and change and as I grow make better decisions.’ It just felt good. What I recognized is the freer I got, the more audiences were connected like, ‘You too! Oh girl okay, now we can really talk.’

New Music

GFM: Are you working on new music?

AG: There’s a song that I wrote called “Choose You Again”. We haven’t released it yet. It’s complete, but we haven’t finalized it yet. DeAndre Shaifer, also known as Dre King, is the producer of the song. It was inspired by my mother and father who’ve been married for 58 years. It really about a lifetime lived with one person that you spend decades with or just a long period of time with and you realize that if you had to do it all over again you would choose that person all over again. The irony is that I’ve never been in a relationship longer than two years. But, I recognize that when I look at all the other non-romantic relationships in my life I realize, ‘Well you have done a lifetime with folks.’ These are also relationships. I look at my siblings and I say that all of nine of them– if I had to do it all over again I would choose every one of them again. It’s a song that sort of celebrates that.

There’s another song called “Higher”. There’s a brother named Vaughn in D.C. He is the leader of a band called Sound Of The City. He wrote this track to “Higher” and it’s a real high-energy song. It speaks to sort of where I’m at now. It’s kind of a continuation of “Now”. It’s like the next level of “Now”. Now that I’ve stepped into being a woman who runs with the wolves, let’s really go for it… really take it to another place of living out loud, being outrageous and stepping into a whole other level. My music producer– James McKinney [and I] we’re prayerfully going to be putting something out towards the end of 2018. We have probably about five songs that are done and we still probably have about halfway more to go.

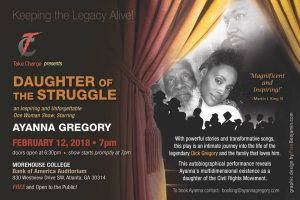

Daughter of the Struggle

AG: I created a one-woman show a few years ago titled, Daughter of the Struggle. It’s a one-woman play about growing up as a child of the civil rights movement. It’s about my father’s life and it’s specifically from the children’s view because too often I think we don’t get the sense of the movement from the eyes, minds and the hearts of the children. So, as one of ten children who grew up in this movement I move into different characters and I embody different members of my own family– my sisters, who at four and six years old were arrested and thrown in jail. That was Lynne and Michele. Two of my sisters– Paula and Stephanie, they were 14 and 15 they were down in Greenwood, MS marching and they really thought they were gonna die when there were guns pointed at them and they were facing the Klu Klux Klan. It’s those stories and then it’s funny stories. Growing up with the death threats and the FBI phone taps was interesting. My parents revealed everything to us so it sort of defanged the whole idea that we could be taken out with the paralysis of fear. We knew that my father was marked. We knew that there was danger and at the same time because my dad was also a comedian, there were ways in which we made light of it. There’s scenes in the play where I talk about my sister Pamela teaching us how to talk to government agents on the phone. [It’s] being funny and silly and trying to stash food from my dad and hide the Now and Laters and the chicken from daddy so he wouldn’t see it. Then [there’s] the story of my father’s transformation from comedy to human rights to health guru, legendary change maker and truth teller and how it sort of trickled down to us. I’m embodying different characters but its specifically from a black girl’s perspective– a black daughter’s perspective. It really deals with my journey of coming into my own and finding my wings as well.

It’s a really powerful piece– specifically for young people and elders. What happens is when I tell this story we do a Q&A after and the elders are usually dealing with the emotion of it because they lived it. Afterwards, a lot of elders are in tears. They’re crying. They want to tell their stories. Then, the young people are amazed that some of the elders with them in the audience have lived this because a lot of the elders hadn’t talked about it. So, it’s a charge to the audience to say, “Mama, Auntie, Grandpa, Uncle– tell your story! Tell your story! Stop passing on the things to your children without passing on the lesson. I do it at a lot of colleges around the country and theatres, but I love when there’s an opportunity to have young people and elders in the audience because it’s an amazing opportunity afterwards for us to come together and hear the elders talk and listen to young people ask questions and share.

The first time I did it in Atlanta was for the Black Theatre Festival. Martin Luther King, III saw it and he just cried. He just broke down. he said, ‘This is really what the movement looked like.’ I think another thing that he said that I didn’t realize is that in him seeing the play, it crystallized for him how much of a father figure my father was for him after his father was gone. I knew he was always around, but I didn’t know that– that he looked at my dad as another father figure. That was really powerful to me.

This play– it continues to change and it’s like a living and breathing libation to his father and his legacy. Every time I do it, the spirit just jumps up in me and I just leave it all on the floor. The first time I did it without my father being her in the flesh was on my birthday in October and I felt him in the room. I’m so grateful that I was able to honor him while he was here. The first time my dad saw the play he just broke down. We brought him on stage afterward and he said that Martin, Malcolm and Medgar never got the hear their children talk about him. I don’t think any of us knew how important it was not just that the world honor him and that his children honor him. I wanted him to know, ‘Daddy, I get it. I get all the sacrifices. Everything you went through… everything we went through… I get it and I got it. So, you can feel safe in knowing that you have passed this baton to children who understand it and who are fully committed to honor this legacy.’

GFM: What is your definition of Grown Folks Music?

AG: Music that’s honest. Music that’s authentic. Music that touches 360 degrees of who we are… where the secular and the sacred come together at the same table and can co-exist. Grown folks music is vulnerable, it’s powerful… it’s love. It’s real love. It’s authentic. It’s soul music. Whatever that means to anybody– it is soul music.

RELATED POSTS

August 16, 2013

GFM Spotlight Interview: Tim Dillinger

June 17, 2011

GFM Spotlight Interview – Adriana Evans

August 22, 2013

GFM Spotlight Interview – Teisha Marie

September 20, 2011

GFM Spotlight Interview – Noel Gourdin

November 24, 2017